Holy Woman's Rage: The “Woman-Life-Freedom” Uprising of Iran

a young woman protesting in Kurdistan, Iran on Mahsa Amini’s 40th memorial.

Holy Woman’s Rage

and the “Woman-Life-Freedom” Uprising of Iran

Her overturned fury…

Holy Woman’s Rage

is a rampaging flood

hands cannot dam.

—Enheduanna in “The Exaltation of Inanna”

Introduction

This short essay is the first in a series called Tears of the Pomegranate [ashk-e-anar], which is dedicated to the women of Iran. This first part unpacks the vital importance of rage as a vehicle of transformation while shining a light on the first female-sparked revolution in history. A revolution that is in the process of toppling one of—if not the—most brutal and cruel patriarchal regimes in the history of the world. I will shine a light on the voices and images that show the immense courage of the Iranian women and girls who have brought awe and inspiration to the world. Secondly, I will amplify with a few figures and narratives of the dark goddess archetype that can help women reclaim anger and rage as an aspect of feminine power. There are many goddesses from antiquity to amplify here, wether we look at what is happening through the ferocity of the Indian dark mother Kali, Black Madonna, the powerful Dakinis in Tibetan Buddhism or the ancient Sumerian Inanna and later Babylonian Ishtar, just to name a few. I have chosen to amplify a couple of these faces of the goddess for this piece that came to me intuitively over the past months, either through dreams or synchronicities. A whole other piece will be dedicated to the female archetypes and warriors of ancient Iran including the Goddess Anahita, about whom I have been writing since 2018.

#MahsaAmini by Reza Zavvri

Mahsa Amini and the Woman-Life-Freedom movement

The day I finished writing this, marks day 85 of the Woman-Life-Freedom [Zan-Zendegi-Azadi] uprising in Iran. A nation wide roar that moved quickly into what is now acknowledged by some world leaders as a revolution. This is not just any revolution, it is the first women-sparked and female-centered revolution known to the history of patriarchy. A revolution that started with women chanting the Kurdish originated slogan Jin-Jian-Azadi (Woman-Life-Freedom) and cutting their hair in the Kurdish city of Saqqez, the hometown of 22 year old Mahsa Jina Amini, who was beaten to death by Tehran’s so called “Morality Police” for wearing her hijab “inappropriately”. Mahsa died in a coma on September 16th, a few days after her arrest. At Mahsa’s funeral, Kurdish women took the scissors in their hand and cut their hair as an old symbolic act of defiance and grief as they raged, wept and mourned while shouting Jin Jian Azadi. The rest of Iran quickly rose up with those words and took to the streets. Iranian diaspora around the world, who enjoy more safety to express their dissent, filmed themselves cutting their hair and standing with Mahsa Amini. Within just a week a roar, a flame took over Iran and Iranian’s hearts around the world. A revolution was ignited.

Background

Not many really expected this, that for more than 80 days now Iranians would not leave the streets, and continue in their defiance and protest against one of the most brutal, tyrannical and violent dictatorships the world has known. I will give few examples to give a sense of what Iranians are up against: In 1988, tens of thousands of political prisoners were executed at the hands of the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ayatollah Khomenei. At the time, there was no internet and he controlled all state media. This silent massacre traumatised a generation but he could keep his image to the rest of the world, and even to the majority of the people in Iran. Fast forward this horror, the regime has continuously imprisoned, threatened, tortured, raped, assassinated and executed any and all people who form an opposition or even raise a voice against the regime. Over the past years, Iranians took to the streets many times and the regime always succeeded to violently crack it down. November 2019 was the previous uprising where the government responded with a bloodshed, killing at least 1500 protestors in three days and cutting off the internet, thus isolating Iranians from the rest of the world while it conducted its gruesome crimes against humanity. And in this current uprising, until today, at least 465 people (including 60 children) have been killed by the regime for protesting or simply being on the street near a protest, while the regime itself denies any deaths due to its violent crackdown. At least 18.000 have been “arrested” and detained for anything between taking part of protests on the streets or posting an instagram story in support of the Woman Life Freedom movement. This number is likely to be much higher with some human rights organisations making an estimate of 40.000. Thousands are being threatened with severe charges that could lead to the death penalty whilst a number have already been sentenced to death. The first execution of a protestor happened on December 8th 2022, an event that shook Iranians once again as the regime showed the world it is willing to use its cruelest weapons to stay in power.

This background, of the level of brutality and cruelty this regime is capable of is important in order to understand the level of bravery and courage Iranian women, students and even schoolgirls have shown us in the past months. I want to make the important note than young men and schoolboys have also risen up and took to the streets. They have taken on a battle with armed forces, a courage and bravery that can only be found in legends and myths. For this essay however, I have chosen to focus on the women’s movement in this revolution and the psychology of the Feminine at this crucial time of the archetypal eruption of the Feminine in Iran after an era of oppression.

Fear of Feminine Rage

Firstly, it is important to address patriarchy’s conditioned fear and consequent shaming around women’s anger and rage. The notion of a “good woman” has infiltrated the world—for example in both Christian or Islamic conditioning, women suffer from a severe suppression of anger and rage. In some cultures that are more ‘feeling type’ cultures like Iran and India, the range of expressions and emotions, its highs and lows are much more accepted than for instance Northern European societies where the ‘feeling function’ is pushed into the shadow.

In either way, anger and rage are considered taboo emotions when it comes to being able to function and be accepted in societal structures. To some extend, it is also a necessity that psychological healthy boundaries and filters are created during childhood development. We simply cannot function in a society or community if we instantly express our emotions like toddlers. But it is important to differentiate places and moments where expressing and using anger is a not only needed and justified but also necessary. There are also times when it is instrumental to change and transformation, of either the individual or collective psyche and structures. It is to these places that I want to turn in this essay.

Vagina Dentata

Regardless of any cultural conditionings, there is a primal fear of women’s anger that is universal to all cultures. This is the fear of Great Mother’s wrath, who can pull us into her tomb at her will. The ancient memory and fantasy of the flood is perhaps the most symbolic manifestation of this wrath. However, there is an extra dimension of fear for this feminine wrath for men which is a deep seated, mostly unconscious one. Erich Neumann describes this as the “shadow side” of the Great Mother and calls her the Terrible Mother. The visceral image of this “terrible mother” is perhaps best depicted in the mythic symbol of the Vagina Dentata. The toothed vagina was made famous in the West through Freud’s coining of the term whose theory was that young men are said to experience an unconscious fear of castration upon seeing female genitalia. While Freud saw the toothed vagina as an ultimate symbol of the Terrible Mother and the masculine’s deepest fear, we have a more mythopoetic understanding of this ancient symbol from the indigenous worldview.

Hine-nui-te-pō by June Northcroft Grant

The Maori culture tells its creation myth with the destructive aspect of the dark Goddess. The god Māui decides to make humans immortal through tricking the underworld goddess Hine-nui-te-pō’s. He turns himself into a worm and crawls into her vagina while she's asleep, imagining that exiting through her mouth would reverse the process of birth and death. But the Pīwakawaka bird witnesses this and begins laughing at this absurd plan and Hine-nui-te-pō wakes up, killing Māui with her obsidian vagina dentata and sealing the fate of humans with mortality. In this creation story, we can see the balancing power of the underworld goddess Hine-nui-te-pō—Goddess of the Night—that comes in to correct the overly solar attitude of the male god and his quest to subvert the goddess’ dark aspect of death to seek immortality. Here, the dark goddess brings balance to the earth by maintaining the laws of creation, and correcting an overly-masculine attitude with her attributed power, that is seated in her vulva.

About 4 weeks into the protests, at the height of the girl’s movement and schoolgirls uprising in Iran, I dreamt the following:

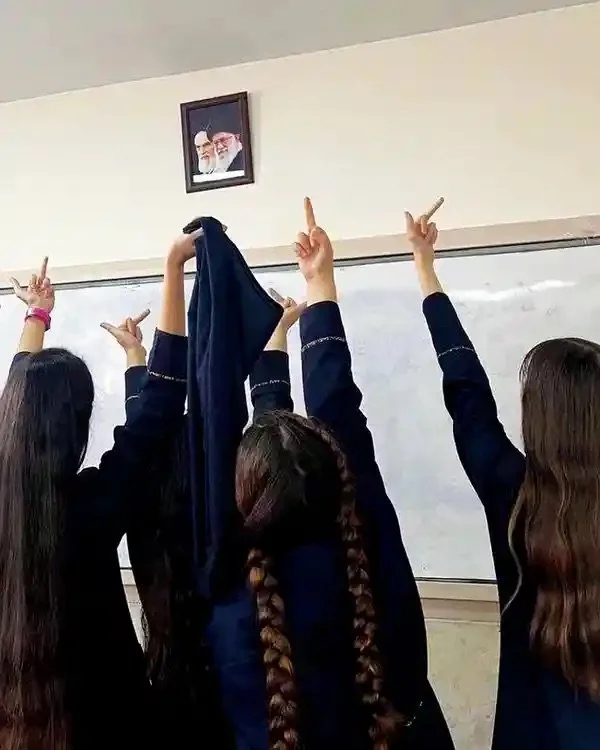

Schoolgirls without mandatory hejab in defiance of the portrait of the Supreme Leaders Khomeini and Khamenei.

“I see the floating head of Khomenei (the founder and first Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic). Then I see a gigantic vagina in front of him. In one swift movement, the vagina sucks Khomenei’s head into herself and swallows him.”

When I awoke from this dream, I was quite amused. One doesn’t need a Jungian psychoanalyst to interpret this dream, the image tells a thousand words as it speaks to our primordial memory. What I found interesting is that this powerful dream came at the height of the schoolgirl’s uprising, a roar that surprised and inspired the whole world. When these young teenagers, with some not even aged 10, shouted, humiliated and kicked out government officials—the world watched in awe. The videos and images that poured out in (social) media have been the testimony of a feminist movement that has risen from the depth, a volcanic eruption of feminine rage and defiance, often also coupled with the same sense of humour that the dream had brought to me. This sense of humour in the midst of suffering and chaos is a mark of the archetype of the dark goddess. She is paradox and play, she is ambiguous and is at ease in the darkest aspects of life and even in the midst of her fire, fury and agony, she can have a great sense of humour.

Following these powerful uprisings at primary schools and high schools, the regime forces entered schools and abducted (“arrested”) many children, threatened or arrested schoolteachers and parents who supported the children so they would keep these dissident children quiet. These schoolgirls are not going to be suppressed for long as from time to time, they still roam and roar in schools and on streets after being released from class. In any case, the images and videos of these roaring girls will forever be engraved in our memory—and this generation will have Zan-Zendegi-Azadi pulsating through their veins and the knowing that they can rise in defiance when they have the chance. They can shout and scream at government officials and kick them out with their united roaring rage.

Rage as a Vehicle of Transformation

Revolution art by unknown artist

It is no longer a secret to our mainstream thought that patriarchy over the past thousands of years—with its crescendo the past few hundred years—has brought to humanity and the living earth many of its current woes. From climate crisis, dictator’s tyranny, extinguishing feminine and earth-rooted spirituality to capitalism and monetisation of human data and the abuse of tech-power; all these forms of oppression and control are rooted in not only the devaluation of the Feminine principle but also the severance of and the abuse of her. It is then, of no surprise that this Feminine principle, or the Goddess, has become incredibly angry. This archetypal rage however is not a regression and is, just like in a personal psychology, a further stage of development. Anger is a flame and rage is an untameable life-force erupting from the depths of the collective unconscious: where there is anger or rage, something is intensely alive. Most of the time, women have to first pierce through the thick layers of dissociation, fear and numbness to even start to reconnect with this vital life-force. Thousands of years of oppression and patriarchy has caused a severe split in women from their own power, and the rage that accompanies this memory of oppression and severance.

The Frog Prince

An example of a fairy tale where the embodied expression of rage acts as a transformative agent is the Frog Prince (2). In this story, the princess befriends and makes a deal with a frog when he helps her retrieve her golden ball which she dropped into a pond. Later, the frog asks to sleep in her bed and eat from her plate while her father re-enforces her daughter to “keep her word”. In the earlier versions of this well-known story, the princess doesn’t simply agree and “embrace the frog” by kissing him, rather, she violently smashes the frog into a wall even when the father orders her to obey to the frog’s commands as she had promised, for “He who helped thee when thou wert in trouble ought not afterwards to be despised by thee.” In this version, it is after the smashing of the frog that he transforms into a prince, and not by means of a compliant kiss! It is important to go back to this early version of the story, before it was adapted to patriarchy’s conditioning and fear of the feminine power and rage.

Her defiance against the “order of the father” is actually the key to her individuation process. It is the false loyalty to patriarchy’s values that keeps women imprisoned and locked away from their feminine power. They dare not go against the “order of the father”, sometimes out of fear but often also out of unconscious feelings of guilt as they feel they would betray the very thing that has “helped her when she wert in trouble.” This infantile loyalty needs to be shattered by a total defiance against it, it is only then that the woman can come into a mature and equal relationship to the Masculine principle.

It is exactly this defiance—where the demanding and invasive frog prince is smashed to the wall—against the “fatherly advice of patriarchy” that Iranian girls and young women are showing the world today. There is however an important difference that makes this Iranian heroine tale into a completely other and in many ways a new one. And that is the level of self-sacrifice these girls and women take willingly and consciously, which is the very thing that has made the world watch in awe. Many of them know that their defiance could lead to imprisonment, torture, rape and death or the very least being wounded and beaten by the police forces on the street. These risks are not a small chance either—this is the imminent risk they know they are at the moment they decide to take to the streets or shout slogans in school. This level of defiance that is coupled with an almost inhuman kind of courage and self-sacrifice is yet to be written in the new emerging story of the rise and redemption of the Feminine. I will be dedicating a separate piece to reflect on this new emerging heroine story.

Collective Rage

Just as in a personal psychology it is important to contain and express anger in the needed moments, or in creative ways like dance, movement-therapy and voice work—so there is also a time and place for collective rage to erupt. This women-sparked revolution in Iran is a prime example of how rage and fury are not only needed, but are vital vehicles of transformation for the collective psyche as well as societal and political structures.

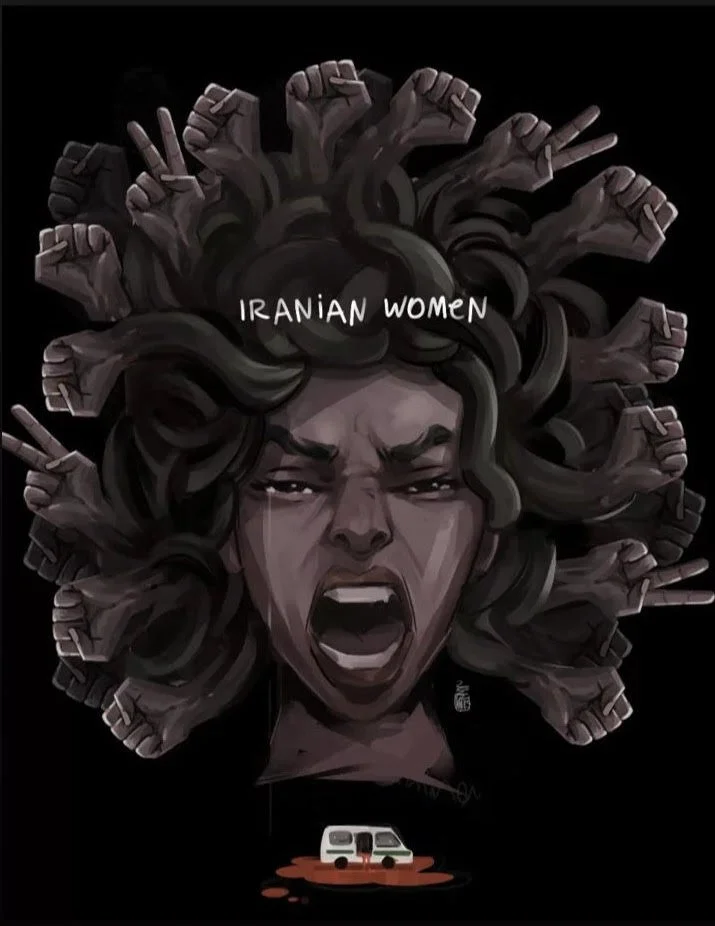

Woman-Life-Freedom revolution art by an anonymous artist in Iran.

Dictators and tyrannical rulers know the power of rage and their prime method to suppress this is to freeze people through fear and shock, which brings in its turn dissociation, apathy and passivity. Fear brings paralysis and results in the ultimate passive attitude in the face of the seemingly almighty oppressor. Rage fuels a fire and becomes an active force, it breaks the shackles of passivity and thwarts us into action. When we are in fear, we reject and withdraw from life which in turn becomes a dark cloud of depression. Anger and rage on the other hand, are signs of an active participation in life. We are angry about something because we care and are invested in it.

When rage and anger help us to stand up for something we value and consciously sacrifice for, it transforms into a labour of love for the cause and automatically pulls us back into life’s currents. Especially for the rise and reclamation of the Feminine, it is important for women to become conscious of patriarchy’s fear of women’s rage and claim back their relationship to it. My personal as well as clinical experience has taught me that anger and rage are facets of feminine power and that reclaiming feminine power cannot happen without reclaiming a conscious relationship these volcanic emotions. One of the ancient texts that can help women to see these emotions reflected in the divine nature of the goddess, and how it is an intricate part of feminine power is in the writings of Sumerian poetess and priestess Enheduanna.

Enheduanna’s Praise of Inanna’s Rage

Enheduanna (2285-2250 BCE) has been argued as the first known poet and author in history. Her writing were hymns and praises to the ancient Sumerian Goddess Inanna, whom she considered herself in service of as her priestess. Throughout her work, and especially in The Exaltation of Inanna, we find Enheduanna praising a warrior goddess that is not only fierce and powerful, but also delights in tumult, chaos and destruction. By praising this aspect of the Goddess, she hopes to please her, calm her down or at other times receive her blessings for victory.

Ishtar (Inanna) on an Akkadian seal (2350–2150 BCE)

“Lioness Inanna

crouched in a reed thicket

leaps to slash the fearless

mountain wildcat

prowling the roads

shows wet fangs

gnashes her teeth

wild bull Queen

mistress of brawn

boldly strong

no one dares turn away

greatest of the great rulers

a pit trap for the headstrong

a rope snare for the evil

where she spits venom

fighting erupts

tumult spreads the poison

her overturned fury

Holy Woman’s Rage

is a rampaging flood

hands cannot dam.”

—Enheduanna in The Exaltation of Inanna (4)

Revolution art by Toni de Muro

The ancient goddess Inanna was a goddess of love, fertility and war. It is noteworthy that this goddess who left her imprints in the collective psyche for over 4000 years was not known as a particularly nourishing Mother Goddess. She was a goddess of power, culture, arts, poetry, love-making and fertility. Inanna (and later Ishtar) was the first goddess figure to rise with the dawn of civilisation and was the main goddess to rule alongside other gods. She was considered the creatrix of life, but not as a classical nourishing and caring mother. Rather, she had the power to create and destroy at her will. Therefore, this goddess compensates the old-fashioned belief that women’s power (and thus role) lies only in their mother-role and that goddesses and the feminine divine are primarily mother-goddesses.

Revolution art: Iran’s map behind and in the torso of a woman

This emphasis is an important one psychologically, as women start to reclaim their feminine power and their capacity to fight and roar. Battle and war have in our modern minds been associated with men. In fact, around the world it is men that are called to war and battle and we attribute all the misery of wars to men’s greed for power or bloodthirsty lust for battle. And yet, antiquity has taught us over and over again that there were female goddesses of war and battle. Men used to praise Sumerian Inanna, Mesopotamian Anath, Celtic Mórrigan and Persian Anahita to be granted success in battle. The fierce and war-like nature of the goddess was not seen as demonic, rather, it was an attribute and a divine power that was needed in human life and civilisation. By taking away the war-nature of the goddess from the realm of feminine, patriarchy has not only deprived women of their power but also deprived civilisations of the kind of battle and conflict that can be in service of life. As a result, conflict during patriarchy has become a machinery of war and conquest that is possessed and drunk on power, completely detached from its higher nature and place in the tapestry of life.

Reclaiming the warrior aspect of the feminine is vital for reclaiming feminine power and the hope to bring balance to a troubled world. Women have to shake off thousands of years of conditioning to reclaim their warrior aspect and find a healthy, conscious feminine relationship to their ability to be defiant, resist and destroy. This, in fact, is our only hope for dying civilisations that has lost its way and purpose a long time ago. The girls and women of Iran are seeding and sprouting this memory in the collective psyche of the world. They are both remembering and helping the world to remember this ancient, warrior aspect of the feminine and its vital necessity for the toppling of patriarchal structures that have been destroying the very fabric and soul of this world.

The Iranian poet Forough Farrokhzad is perhaps best described as the Iranian “Enheduanna meets Anais Nin” as she combines these feminine essences into a singular voice of feminine power, desire and agony all combined. Her poetry is the voice of the Iranian soul, echoing her depths of fertility, agony and fury. The following poem I dedicate to my Iranian sisters and mothers at this crucial time:

Revolution art by Shaghayegh Safaei

Call to Arms

Only you, O Iranian woman, have remained

In bonds of wretchedness, misfortune, and cruelty;

If you want these bonds broken,

grasp the skirt of obstinacy

Do not relent because of pleasing promises,

never submit to tyranny;

become a flood of anger, hate and pain,

excise the heavy stone of cruelty.

It is your warm embracing bosom

that nurtures proud and pompous man;

it is your joyous smile that bestows

on his heart warmth and vigor.

For that person who is your creation,

to enjoy preference and superiority is shameful;

woman, take action because a world

awaits and is in tune with you.

Sleeping in a dark grave is happier for you

than this abject servitude and misfortune;

where is that proud man…? Tell him

to bow his head henceforth at your threshold.

Where it that proud man? Tell him to get up

because a woman is here rising to battle him;

her words are the truth, in which cause

she will never shed tears out of weakness.

—Forough Farrokhzad (translation by Michael C. Hillmann)

Footnotes

Erich Neumann, The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 168.

Collected by the Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 in Grimm's Fairy Tales (KHM 1).

Betty de Shong Meador, Inanna: Lady of the Largest Heart, p. 119.

You can find more poetry of Forough Farrokhzad here.

Bibliography

De Shong Meador, Betty (2000), Inanna: Lady of Largest Heart: Poems of the Sumerian High Priestess Enheduanna, Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press.

Neumann, Erich (1994), The Great Mother. Princeton: Princeton University Press.