Seeding Pomegranates: Yalda, Winter Solstice and Living With the Dead

Photography Art by Asal Jelveh

Seeding Pomegranates

Yalda, Winter Solstice and Living With the Dead

POMEGRANATE [Anaar انار]

It was my grandfather’s favourite seasonal activity. To break open the pomegranates and separate the seeds thoroughly. The many kilos of pomegranates had come fresh from his hometown near Yazd, located in the desert-like landscapes of Southern Iran. My paternal family owns a small piece of land near the ancient town of Yazd, where generation after generation tended and enjoyed juicy pomegranates from its trees. My grandfather was always a proud man when his pomegranates arrived in Tehran; blood-red and crisp, just as they are supposed to be. He always looked forward to “seeding” the pomegranates, doon kardan as we say in Farsi. As a child, I used to watch him; sometimes he would teach me the tricks and sometimes we would sit in silence. It was a hypnotic and timeless experience, to watch those old and rough hands seed the pomegranates into a big glass bowl in the most refined and thorough way. He never left out a single one of those juicy winter rubies (Yaghoot-e-Zemestan یاقوت زمستان) and you would not find a trace of the white peel in the bowl of red rubies. Later on, when we were uprooted form Iran and living in The Netherlands, not a Yalda night went by without me eating and spending the night with this heavenly fruit. For us Iranians, the pomegranate has always been a symbol of light and joy for the dark night of Winter Solstice.

Yalda: The Iranian Winter Solstice Celebration

On Winter Solstice known as Shab-e-Yalda or Shab-e-Chelleh, you will find Iranians all over the world celebrating and gathering together. Not to welcome the winter, but to welcome the rising of the light after the longest day of the year in darkness. This ritual and celebration comes from our ancient Zoroastrian heritage and has roots going back to the even older Mithraic tradition of Iran. This night has been celebrated for no less than 5000 years by our people. On this longest night of the year, Iranians gather together to drink red wine, eat dried fruits and nuts and most importantly red fruits that symbolise the sun—like pomegranates and watermelon. We tell stories and read divination poetry from Hafez. The idea is that you stay up all night to court the sun at dawn and to celebrate the victory over the dark. The ancient Zoroastrian religion was deeply invested in the duality of light and dark and the triumph of light over the dark forces of Ahriman, who represents the evil twin to the God of Light Ahura Mazda. The old-Persian, Avestan word for this night was believed to be Zayeshmehr: the birth of the Sun, or Mithra (Mihr/Mehr). This old name of Yalda most likely goes back to pre-Zoroastrian times where it was believed that Mithra went through a death and rebirth during the Winter Solstice.

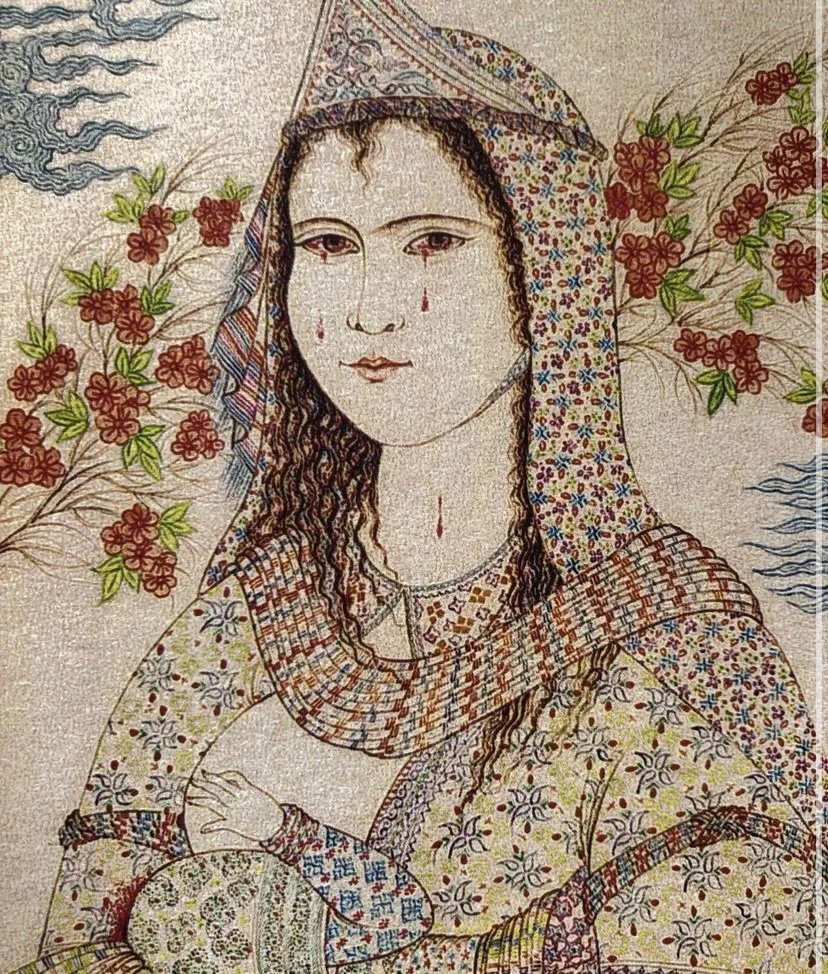

Revolution art by Reza Jozani

Bleeding Pomegranates

This year’s Yalda wasn’t a celebration of light, but rather one where Iranians all around the world were plunged into the depths of the symbolic significance of this night. What does it mean to wait for the sun to rise in the darkest of days? What does it mean to hold the light of hope, while the world around you darkens with despair? How do we blow on the flames of life when a monstrous machine of death has unleashed its army? This year’s pomegranates didn’t symbolise the rays of sun and the glow of life but rather, the tears of blood that have been shed by the many victims of a murderous tyrant. “This is the year of blood!” chant the protestors of the Woman-Life-Freedom revolution, “We will overthrow Khamenei!” And indeed, it has been a bloody 3.5 months ever since Mahsa Jina Amini died at the hands of the morality police and a fury unleashed in Iranian’s hearts and streets. The digital artwork movement that has been a pillar of this unfolding revolution was steeped in the reds of the pomegranate, bleeding red rivers and tears of blood.

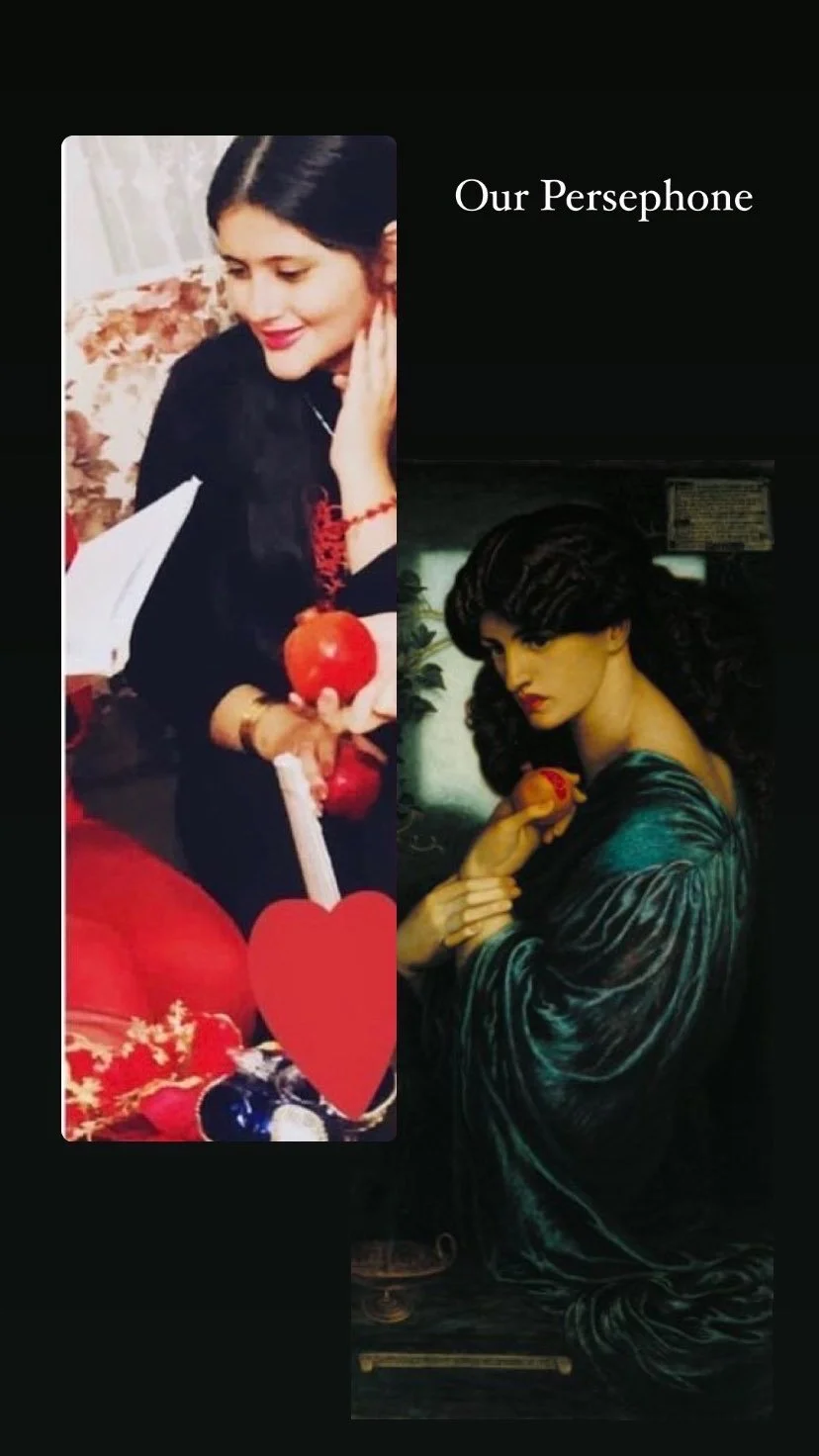

In the Name of Yalda

Synchronicity had its way with us this year and added salt to the wounds we all felt on this night. Social media reminded us that it was both the birthday as well as the 40th day of mourning or Chelleh of Yalda Aghafazli. Yalda was a 19 year old girl who went to one of the #MahsaAmini protests and got arrested on October 26th. She was released 10 days later after being tortured for confessions and remorse, which she refused. But this heroic tale ends tragically after she allegedly took her own life 5 days after her release. There have been reports of the prisoners being drugged heavily before their release so wether she took her own life or was killed, will remain unknown for now. What we do know is that she lost her life at the hands of this cruel regime just before she would turn 20. That her birthday, the Yalda night, would coincide with her 40th day of memorial, her Chelleh—which is an important day of mourning for Iranians— is a synchronicity to behold. The Night of Yalda (Shab-e-Yalda) is also called The Night of the Fortieth (Shab-e-Chelleh), referring to the night before the first 40 days of Winter that end in another significant celebration. This synchronicity of Yalda’s death, birthday and chelleh-memorial made the revolution art movement explode on the day of Yalda which resulted in some of the most symbolic works of art of this revolution.

Persephone

What is the story this synchronicity wants to tell us? Looking at these images of Yalda, I could ofcourse not stop thinking about the ancient Greek myth of Persephone, who becomes Queen of the Dead after being violently abducted by Hades to the Underworld.

In this ancient Greek myth, the maiden Kore is abducted by her uncle Hades, the god of the Underworld, after the marriage was approved by her father Zeus without the knowing of her mother Demeter. When Demeter finds out about Kore’s abduction, she rages and mourns endlessly and eventually stops nourishing the Olympian gods and humans. As a result the lands and people suffer from drought and famine. Demeter refuses to be the nourishing goddess that she is, unless she is given back her daughter. The story is filled with many transformations of both humans, the goddess herself and the community of Eleusis. Eventually, Demeter is given back her daughter and life starts blossoming with their reunion. Persephone, Queen of the Underworld and no longer little Kore, is now the wife and consort of Hades. Because she ate six seeds of the pomegranate given to her by Hades, she has to seasonally return to the Underworld.

Whenever I have seen the symbol of the pomegranate linked to Persephone, I have always pondered on Persephone’s mythic link to the ancient lands of Persia. We know the Greeks and the Persians had their way with each other as both destruction, envy and creativity moved in both directions. Since the pomegranate has originally been traced back to Persia and from there made its own journey to both the East and West, it could well be that the mythic mycelial network of Persephone finds herself in Persian soil. But onto this date, I have not been able to historically trace the symbolic network of Persephone and her pomegranate to ancient Iran besides the symbolism of the night of Yalda itself.

This year however, this link was made ever so visible to me through the Iranian women-sparked revolution. Yalda Aghafazli brings Persephone to the Iranian women. As a freedom fighter and young maiden that lost her life to the Underworld, she is to all of us the Queen of Yalda and will forever be remembered as one of our maiden-heroes. She was violently abducted, taken to the Underworld of Iran’s tyrant and endured torture that you and I would not even dare to imagine. She returned, ever so briefly, to the upper world before she was pulled into realm of the dead. It is in Iranian’s remembrance of her that she will return to the upper world, even if for a winter night, with every Yalda celebration from this year onward.

Mourning Mothers

Just like the mourning of Demeter as mother of Persephone shakes up the everyday life of the Greeks, so have the cries and moans of the mourning mothers of Iran pierced our hearts and taken over our minds day and night. Images of mothers wailing, moving their bodies to their own roars and moans, laying next to their children’s graves with their hands buried in the earth….these are images we will not forgot, and certainly not forgive easily. The grief of Demeter this year has taken over Iran. The average age of the protestors being under 20 years old, makes this revolution and its fallen heroes the youngest one ever seen in the history of the world. I have been telling the story of Persephone every year since my own mother died in 2016. Engaging in this seasonal myth-telling has been a deep experience in my years of mourning and grief. Each year’s telling and work with the myth has its unique stamp as working in the traditional mythic oral arts is much like being immersed in nature. You can walk by a tree in your local forest a hundred times and never will it be the exact same experience. But after seeing the images and videos of so many of our mourning mothers, I know that this year’s myth-telling will have a distinctly different weight and texture to it. There is something about a mother’s wailing that shakes our bones and carves our souls.

Revolution art “Mother” by Farah Ossouli

Video art by Manah Gharahkhani with fragments of mourning mothers and fathers.

Mahsa Jina Amini on a Yalda night and Persephone by Thomas Hart Benton (1939)

Mahsa Jina Amini: Our Queen of the Dead

And finally, another Persephone that caught my eye on Yalda was Mahsa Amini herself, who has become the symbol of the Woman-Life-Freedom revolution. An old photo of her was released by her family on Yalda, where she resembles the Queen of the Dead herself in the famous painting of Thomas Hart Benton. Mahsa Amini, in whose name and symbol more than 500 people have died and at least 18.500 jailed in the Underworld of the Islamic Republic, has certainly become the Queen of the Dead of this unfolding revolution.

It is in these small symbolic moments of synchronicity that I find solace. These meetings of the timeless with time and the sensing of a pulsating mythic meridian don’t make these days less dark or painful nor does it sugarcoat the cruelty and agony of reality as it unfolds before our eyes. Rather, it helps create a container to be present to the darkness and pain without having to dissociate from its immensity. When we find stories that are like underlying currents to these horrendous events, we can hold that story which in turn, even for moment, holds the darkness and weight for us. It helps us bear a little bit more, a little bit longer. Rather than feeling isolated and removed from the rest of the world, it helps us remember that these stories have always been part of the archaic memory of humanity and that we too, are a living part of this ancient mycelial network of stories stretching back into time and place and ever returning with their fragrances of darkness and light.

Revolution art by Roshi Rouzbehani

“Still with all the pain

Hope is the cure,

for in the end,

there is an end to the night of Yalda.”

— Sa’adi