Initiation by The Crone in Psyche and Eros

Cupid and Psyche (1821) by Giuseppe Cammarano

Initiation by The Crone

encountering the dark goddess in Psyche and Eros

The story of Psyche and Eros is a favourite amongst Jungians and consequently has been widely interpreted, looked at from various perspectives. It is to Marion Woodman and Elinor Dickson’s interpretation on this story that I turn, from where I would like weave and amplify with a Persian fairytale, while circumambulating the figure of the goddess in her Crone aspect.

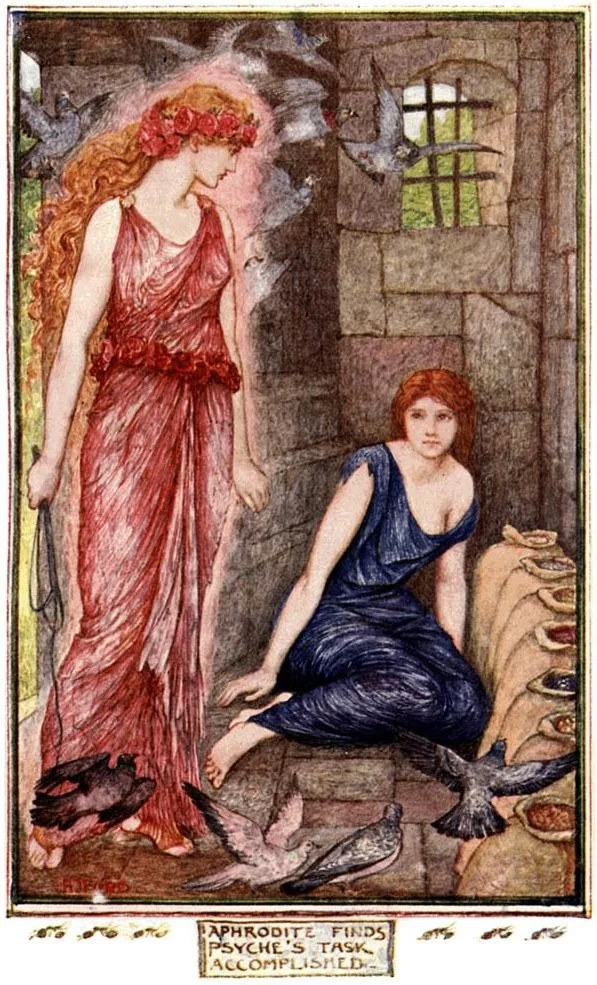

In the book Dancing in The Flames, Woodman and Dickson write about Psyche and Eros in the chapter about the wisdom of the crone. They see the goddess Aphrodite here as an expression of the dark goddess who initiates and matures the feminine psyche through a set of tasks and challenges that seem impossible, and rather cruel.

“Aphrodite finds Psyche’s task accomplished” by Henry J. Ford

“Aphrodite’s severe and unfeeling demeanour may seem cruel, but in fact she, as dark goddess, is the catalyst that brings out all strength, defiance and individuality that sleeping Psyche never had.” (Woodman and Dickson, p. 130) This cruelty has to be carefully differentiated from that of the negative mother that can also haunt a woman and her interior life. In this story however, each task is serving a purpose to help Psyche grow in her character, and thus differs greatly from the deathly voice of criticism and condemnation in a negative mother complex.

A fairytale that shows the differentiation between the negative mother, sometimes referred to as the ‘death-mother’ and the ambiguity of the dark goddess is found in a Persian Cinderella story that goes by the name Mah Pishooni (Moon Forehead). This story also illustrates how these two poles of the dark feminine—from red to the ultraviolet side of the spectrum—can work together in a woman’s individuation journey.

THE STORY

In Mah Pishooni we find a story that teaches us about initiation and about the wisdom of walking into the unconscious with an attitude of humility and service and, in some well timed moments; the right kind of trickery.

Mah Pishooni loses her mother like in all Cinderella tales but in this story the mother dies as part of the grand evil plan by the future stepmother, Mah’s schoolteacher Mollahbaji (a religious title for Islamic educated female authorities). Mollahbaji, finding out about the good financial situation of the father, decides to manipulate Mah to push her own mother in a jar of vinegar and so makes an empty place that can then be filled with a stepmother. Little Mah is swayed by her charm and the plan is fulfilled. But soon, after Mollahbaji gives birth to a half-sister, she treated horrendously and is being given a series a very difficult tasks by Mollahbaji. And just like Psyche, Mah too quietly suffers them, often weeping in despair upon which unexpected forces in the form of animals come in to help her. The most important animal is a yellow cow that after some time, appears in the jar of vinegar where her personal mother once was shoved into.

During one of the tasks, she is given a sack of cotton to thread and spin while she takes the yellow cow to pasture. The wind blows her cotton balls into the well upon which she is guided by the benevolent cow mother to go into the well and find her cotton in the house of an old hag in the hidden forest at the bottom of the well. She is told by the yellow cow to greet the old woman and to do what she says or, in some versions to do the opposite of what she says. The wisdom of the cow mother gives little Mah not only the courage and guiding wisdom to go on into the darkness of the underworld.

When she arrives at the old hag’s house she greets her politely. In some versions the old hag is somewhat fierce and crazy and asked Mah for very unusual tasks like throwing a rock at her head. Her cow mother has warned her that she must do the opposite so she starts combing the old hag’s hair upon which cockroaches come out from it. But she perseveres and gives the old lady the care and disentangling she needs. The tasks continue and little Mah finds herself cleaning a very dirty house and courtyard, and even praising the old woman for being much cleaner and more beautiful than her stepmother. The old woman then directs her into the room next door to find her cotton. When she enters the room, she sees it is filled with wonderful jewels and golden coins, but she only takes her cotton balls and goes back. The old hag sends her off into the first, second and third garden that leads onto a magnificent river. She is told to bathe in the river and wash her face with it. After she does that, she is astonished by the beauty of her own face in the reflection of the water, where she sees that she now has a glowing crescent moon on her forehead and a star on her chin. She is sure to hide it well when she travels back home and carries on with her chores. The stepmother eventually finds out and demands that Mah takes her half-sister to ‘get one of those too’.

But the half sister fails miserably as she does not have the guidance from the yellow cow nor does she have the humility, patience and devotional attitude that Mah has. She enters the house of the hag with demands, impatience and rudeness. She insults the dirty old woman and, being focused on her goal only, doesn’t want to clean the hair of the hag and her house as thoroughly as little Mah did, and even insults the old woman for being disgusting. When she is directed into the room next to find her cotton, she is mesmerised by all the sparkles and grabs the jewels and coins, almost forgetting about the cotton. When she then bathes in the same river, she finds in her reflection the most horrendous sight; a donkey’s penis is growing out of her forehead and a scorpio’s tail out of her chin.

[End Part 1 of the Story - for the full story see my essay on Mah Pishooni]

What this story helps amplify is the development of the dark goddess or the crone in the psyche of a woman. What is interesting in this story is that the benevolent cow mother did not come from Mah Pishooni’s innocence or goodness only, it came from her own magnetic pull towards the dark feminine, first in the shadow form of Mollahbaji, who is the one that prompts her to put her own mother to death by shoving her into a jar of vinegar. Mah Pishooni is therefor the one that helps to bring the dark feminine into her own house and life. I like this version of Cinderella as she is not just the innocent little girl who has fallen victim to a dark mother, but has a role in it, much like Psyche has in the moments of defiance against both Eros and Aphrodite. It illustrates how psyche is always seeking wholeness and how we are prompted in life to engage and be lured by the shadow as it is here that we could find the key our individuation journey. Mah Pishooni cannot find her own authentic, direct connection to the Mother archetype if she first does not symbolically reject her personal mother. It is only when she is suffering at the hands of her stepmother that her unconscious symbioses with the personal mother is being transmuted (inside the jar of vinegar) into a relationship to the archetypal Mother, symbolised by the yellow cow.

The task of integrating the ambiguity of the dark goddess and the crone, started with the suffering of little Mah under Mollahbaji. Here, the cruelty of the step-mother has helped Mah to endure suffering and find inner strength in moments of despair. She is thus well prepared for an encounter with the crone at the bottom of the well. She carries out the tasks almost effortlessly and due to her connection to the wisdom of the archetypal Mother, she is given the mark of the goddess by the magical river (this story connects back to ancient Persian goddess tradition of Anahita, Iran’s matriarchal river Goddess). On the other hand, her step-sister is caught in the negative mother and is identified with her, rather than being in a relationship to her, and thus fails miserably at encountering the archetypal ferocity of the crone. She falls prey to the greed and critical voice of her internalised negative mother and makes all the wrong choices in her encounter with the crone. This story illustrates quite literally Jung’s words about our attitude toward the unconscious: “We know the mask of the unconscious is not rigid—it reflects the face we show it. Hostility lends it a threatening aspect, friendliness softens its features.” (Jung, CW12, para 29.)

In Psyche and Eros, we see a similar interplay of shadow, envy and trickery with the feminine figures around Psyche that are all part of the initiatory steps she has to make in order to find the inner strength that lies dormant within her. She is prompted by the shadow to awaken from her unconscious union to the animus, she is challenged to find the inner image of the Self as Feminine, rather than being overly reliant on the outer (or inner) animus and into complying with the masculine principles that are put on her. To quote Woodman and Dickson:

“With no inner Wisdom figure to guide them, and no outward model to help them set boundaries and be their own person, young women fall victim to false and superficial ideals, such as pleasing others. Ironically, they achieve their greatest success at the cost of their own emerging sense of self. […] Many women are locked into relationships that leave no room for their own creative expression. In fact, they are not even aware of their own creativity. Without the Crone—that part of us that can stand alone— many relationships stagnate in codependence, in which both partners act out carefully defined roles that block growth.” (Woodman and Dickson, p. 140).

GODDESS MYSTERIES

To me, both these stories feel to have an echo of the old goddess traditions. As mentioned before, the tale of Mah Pishooni is steeped in symbols of the ancient Persian goddess Anahita, who was a pre-Zoroastrian fertility goddess to whom temples and objects of worship have been found. The feminine mysteries that accompanied goddess worship were rooted in the oral traditions, and so it is through these fairytales that we can fork out echoes of what the initiatory journey for the young woman entailed. In Psyche and Eros, we find similar echoes to which I would like to turn briefly.

In the beginning of the story, we see that the goddess is angry because humans are not worshipping her anymore, but rather the human Psyche. Her temples are emptying and she needs to put a stop to this. Psyche is condemned to marry the monstrous serpent of the underworld by the Oracle of Apollo and the drama further unfolds from this dreaded destiny. If we look at this initial set-up, we can find a few important motifs and clues about the hidden goddess mysteries seeping through.

First of all, Aphrodite is angry due to her temples being abandoned and all attention going toward a human woman that has forgotten that her beauty and radiance comes from the goddess herself. This archetypal rage can historically be understood as the goddess worship declined in favour of the rise of civilisations and the shift away from the feminine mysteries. She then condemns her to a marriage to the dreaded underworld serpent. This motif however, used to be part of the goddess cults in the ancient greek mysteries of Delphi. There, the Oracles of Delphi were symbolically wedded to the serpent of the underworld, known as Python, with whom they would be in a state of trance and possession when they would enact as oracles. It is only later that Apollo comes as a masculine hero god to slay the serpent and take over the Delphic mysteries in favour of an Apollonian one. To be destined to wed the ancient serpent then, is to be (forcefully) initiated into the goddess mysteries, in order to remember the origin of her extraordinary beauty and lonely destiny. The Oracles of Delphi did not have a marital life and their occupation came with the burden of responsibility and limitation to be the Oracle servant, rather than to live an ordinary human life, symbolised here by Psyche’s sisters. In this light, we can say that Psyche was being awakened to the ancient feminine mysteries and the occupation as priestess and oracle, initiated by the goddess herself.

Last but not least, it is important to note that this story was written by Apuleius in his famous work of The Golden Ass, which is in itself a piece written and centred around the goddess mysteries. He was himself an initiate of several mystery cults, including the Dionysian Mysteries. There are a variety of scholars that trace the story to folk and fairytales from different regions. However, this specific version has only been found and preserved in Apuleius’ work, perhaps because this (retelling) of an older tale was the creative work of imagination by Apuleius, woven through the larger narrative of The Golden Ass and the Isis mysteries.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jung, Carl G., (1993) [1944], C.W. 12: Psychology & Alchemy, R. F. C. Hull (trans.). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Woodman, M., & Dickson, E. J. (1996). Dancing in the Flames: The Dark Goddess in the Transformation of Consciousness. Toronto: A.A. Knopf Canada.