Power & Shadow: Khomeini, Ahriman and the Archetype of the Trickster

Power & Shadow

Khomeini, Ahriman and the Archetype of the Trickster

Khomeini and the Shi’a Trickster Concept of Khod’eh

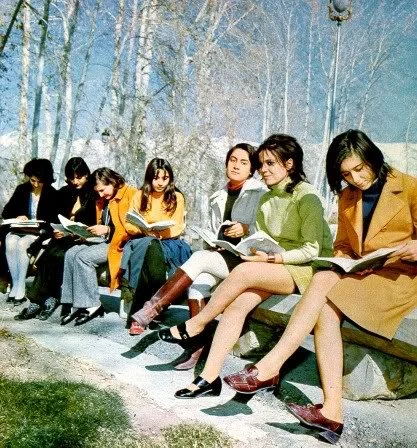

Many people in the West—including Iranian diaspora who grew up outside Iran—wonder how a modernised Iran from the 70s could have turned into such a radical Islamised theocracy. If you search for photos of Iran in the 60s and 70s, you will quickly find pictures of women walking freely in mini-skirts in Tehran and men with their tight flared pants and big moustache, an image that could have been captured in Paris or New York of that time. The question of how mullahs came to power in Iran is a complicated and historical one—stretching back to the invasion of Arabs and Islam in ancient Persia. There is however, one simple way to answer the turn of events in 1979 and how Iran became the Islamic Republic of Iran that ended 2500 years of monarchy. One answer to this is that Iranian revolutionaries of 1979 were tricked by a master trickster: Ayatollah Khomeini.

To understand how he came to power through trickery and deceit, we must time-travel in our imagination to a time where information and media were not available at the tip of our fingers. States could (and did) easily control media nationally and therefor could more easily keep people isolated from the rest of the world—and from each other.

Iran at the time had a famous king called Shah Reza Pahlavi. He had great plans for modernising Iran which was well visible through the image Westerners had of Iran, the Shah and the glamorous queen Farah Diba. If you ask the average European above 60 years of age, they can tell you how impressed they all were about Iran in the 70s and remember to great detail the “greatest party in the world” the Shah and Farah Diba gave for world leaders in 1971 to celebrate 2500 years of monarchy in Iran. Little did they know however, that it was to become a farewell party of this ancient monarchy in less than ten years. This decadent party in the middle of a desert did not go without critique from the people. How could he spend hundreds of millions (allegedly) for the elite of the world while many of his own people still lived in poverty?

But this “greatest party in the world”, although an important symbolic event in hindsight, was not the reason the Shah fell. It was his “one-man” rulership without a democratic check-and-balance that was creating a growing opposition; from democratic freedom-fighters to communists and of course the clergy with Khomeini as leader. The Shah had tight control over his opponents and tolerated no opposition, and while many high ranks could be critiqued or mocked, there was no space at all to say anything about the Shah without risking serious repercussions. Though he was himself at times threatened by the clergy and gave them spaces of authority and power, he held a tight grip on anything that came from the then exiled Khomeini, who had started a smear campaign against the Shah in the years before his exile. Of importance is here the book Khomeini had written in his years of exile called “Velayat-e-Faqih” which lays out the structures of a new Islamised state in Iran. A book which came to shape Iran after the Shah’s fall.

Many revolutionaries—including my father—who were tired of Shah’s dictatorial traits, had not even read this book as it was censored and unavailable to the average Iranian. “Had I read his book, I would have never gone into the streets!” my father said in a recent discussion with a frustrated voice. “We were all tricked! And Khomeini even admitted it himself!” he then said to me with a painful, strange smile on his face. I noticed something about my father’s smile….was it disguising his deeper pain and trauma of having been fooled so naively and feeling guilty towards the next generations? Or maybe even a secret fascination for this level of trickery? Perhaps a combination of both. So what did Khomeini do to trick an entire nation?

Khod’eh: a Shia Concept of Trickery

Khomeini told the free West in many of his interviews and talks to the international leaders that he wanted to bring a full democracy to Iran. In fact, the Islamic Republic of Iran would show the world how democratic an Islamised state could really be, how progressive it was for women and how well it would glue with the Western world. But, those that had read his book “Velayat-e-Faqih” knew all of this to be utter nonsense. He had laid out Shia law extensively and women’s rights would know a dreadful downfall from the laws that existed in Iran back then which were pretty progressive compared to even many Western countries. Khomeini’s stern and stoic persona simply had two faces—or rather two voices: one for his followers, radicalised Shia muslim like himself, and one for the free-loving revolutionaries like my father and the Western world. He turned to each and said what they wanted to hear, and he got away with it. In a later interview, when he was confronted with his false promises of democracy and women’s rights, he simply admitted he employed a tactic of deceit called “khod’eh”. Khod’eh is a Shia concept of “tricking one's enemy into a misjudgment of one's true position.” (A. Taheri) Thus in 1978, Khomeini told the British daily and The Guardian, that he was not interested in having “the power of government in my hand.” Many analysts thought he would retire to the Shiite seminaries of Qom, after he returned to Iran. But none of this was true and he gradually and rapidly seized a power that would be even more dictatorial and oppressive than that of the Shah.

There is little to nothing written about this concept of Khod’eh from a depth-psychological perspective, but I will attempt to look at this through both Jung’s writings on the archetype of the trickster and a mythos-religious perspective in Zoroastrianism, the religion that grew from the soil where this greatest deceit of the Iranian people took place.

Ahriman: the Zoroastrian Trickster Devil

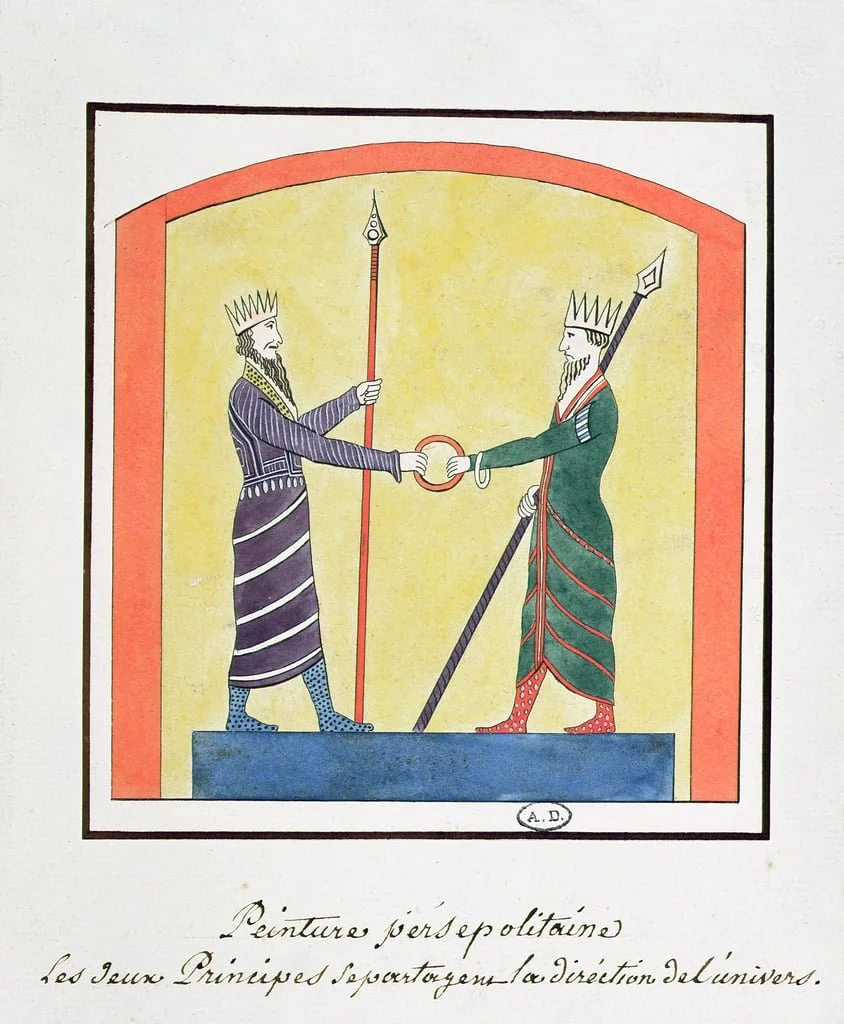

Ahura Mazda and Angra Mainyu dispute the world, copy of a frieze from Persepolis

In the ancient Zoroastrian creation story, the God of light and wisdom, Ahura Mazda, has an opponent who was born at the same time as him. His name is Ahriman, he is the dual and opposite of everything Ahura Mazda, or Ohrmzad, represents. Where Ohrmzad is light, truth and wisdom, Ahriman is darkness, deceit and ignorance. Many refer to Zoroastrianism as the first monotheistic religion of the world. But this is essentially incorrect or at least not a complete picture. It is the first dualistic religion, where there are two opposing cosmic forces at work in the universe: the God of Light Ohrmzad is equal to the God of Ignorance and Darkness Ahriman. Some scholars argue that it is in fact this dualism that sparked fear that ultimately created the Abrahamic religions that promoted monotheism, the God of Light and everything good being the highest and ultimate truth—and the god of darkness, or Satan, being the trickster who deceives the good believer. Elements of the latter do have their origin the Zoroastrian creation story of the first human Yima (or Jamshid in Shahnameh) but the origin of the Divine in this ancient religion, starts in fact in dualism. I prefer the nuanced interpretation that the Zoroastrian religion is “combines cosmogonic dualism and eschatological monotheism in a manner unique to itself among the major religions of the world.” In other words: Zoroastrian religion shows that from the primordial ouroboric consciousness emerges a duality, a tension of opposites, which can become unified in the image of the God of Wisdom Ohrmzad, who would represent the Self from the Jungian perspective.

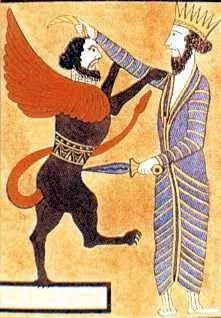

Ahriman being conquered by Ohrmzad [Ahura Mazda]

What is noteworthy about the dark twin Ahriman, is his level of trickery and deceit in the Zoroastrian creation story. Through deceiving and lying to Yima, the First Man, he manages to create doubt in his mind that leads to him losing his “Light of Glory” (Far/Xvarnah) that makes him immortal. He can then strike and kill him as he has become a “mere mortal”. One could say, from a psychological perspective, that it is the trickster that brings the human “down to earth” and into his humanity. He is no longer an immortal being that is separate from the forces of creation, but is planted in the soil of the earth as a “mere mortal”. In fact, in this creation story each element of creation (plant, animal, man) falls from its unique position of living in solitary glory to becoming multiplied after Ahriman destroys each. From an alchemical perspective, we could argue that Ahriman is the catalyst or the element of “opus contra natural” — the moment we have to go against nature in order to make a leap in consciousness. Here, Ahriman is the destructive force that annihilates life, upon which not only one rebirth but a multiplicatio of new life happens. After Ahriman strikes each of the glorious “single” creations of Ohrmzad, the Earth Angel brings the dead matter through an alchemical process that eventually creates all the vegetation, animals and humans of the world. Without Ahriman, the dark trickster, this earthly abundance and multiplication would have not been catalysed in this deeply alchemical creation story.

The Trickster Archetype

“The devil is the father of all tricksters.”

Jung has written extensively on the trickster. He was especially concerned with this archetype due to its importance to the individuation journey, and its exile in Christianity. As a shadow figure he argued it was the catalyst that could awaken the human psyche into his or her own dual nature and thus the initiate the process of individuation. He said that it was “the diabolical aspect of every psychic function that has broken loose from the hierarchy of the total psyche and now enjoys independence and absolute power…”. As a complex that is completely dissociated [and thus “free”] from the personality, it is utterly difficult to control—and therefor become conscious of. Many people throughout their lives project this part of the psyche onto the outside world and can live a relatively calm and controlled life. It is when we are in the grip of this inner-trickster that our lives can become tumultuous. This is the moment the duality of our own nature can reveal itself in the mirror and therefor a call to individuation and wholeness can be heard. But let us look for a moment to the archetype of the trickster at a collective level. What happens on a micro-individual level, can also happen to some degree to the meso-level of the group. What does it mean when an entire nation is in the grip of a shadow figure? Is it possible to individuate as a society and move toward the reconciliation of opposites as a culture? What is happening in Iran with the unfolding Woman-Life-Freedom revolution is a true constellation of opposites; the feminine, life affirming power and call to freedom vs. the patriarchal, oppressive and diabolical regime of the Islamic Republic. These two opposites could have not been more stark and unlike any of the other revolutions in the world, this revolution is sparked and led by the Feminine, making the oppositions (and thus the conflict) even more dramatic. But let us return to the key figure and catalyst of this regime and look at what aspects of the trickster he represents, and what meaning we can make from this shadowy and darkening period he brought when he set foot in Iran 44 years ago.

At a first glance, we can see that Khomeini offers striking resembles to the ancient archetype of the trickster. Jung writes:

“A curious combination of typical trickster motifs can be found in the alchemical figure of Mercurius; for instance, his fondness for sly jokes and malicious pranks, his powers as a shape-shifter, his dual nature, half animal, half divine, his exposure to all kinds of tortures, and—last but not least—his approximation to the figure of a saviour. (3)”

The trickster represents the lowly self within the human psyche, the uncivilised amongst and within the proud and civilised.

“He is obviously a “psychologem,” an archetypal psychic structure of extreme antiquity. In his clearest manifestations he is a faithful reflection of an absolutely undifferentiated human consciousness, corresponding to a psyche that has hardly left the animal level.”(4) — Carl Jung

The Jester

It is perhaps for this reason that the old royal houses always had a jester—the original clown— by their side. The jester was given a high position in the royal court and was the only one who had the authority to not only stand alongside the King and talk and mock freely without being punished. They enjoyed protection that was symbolised by what their attire that mirrored the monarch’s: a crown (cap and bells) and a scepter (marotme). This mirroring image of the “fool” or trickster had a profound psychological impact that is not to be underestimated. The serious, proud and highly civilised King had a double that was his mirror-image: foolish, ridiculed, ridiculous, unbound and wild. The symbol of the Self, of Ohrmzad, was mirrored and compensated by its double and dark twin; his opposite and shadow, his twin brother Ahriman. The inclusion and containment of this shadow figure next to the ruling monarch, brought a balance that worked in favour of both the monarch and its people.

Until before the rule of the Pahlavi dynasty, Iran too knew its own variant of the jester, called dalghak-e-darbar [دلقک دربار ]. For some reason, this tradition dissolved and we could say, so grew more dangerous the arrogance and suffocating pride of the King, a well-known warning in Iran’s most famous literary works, the Shahnameh [the Epic of Persian Kings]. Myth after story after legend, the corruptible powers of Kings are seen unfolded in curious details, warnings and battles. In many ways, one could argue that Shahnameh, besides being an important collection of remnants of ancient Iranian myth and fairytales, is a long story about the corruption of power and pride; one of the main dangers and shadows of civilisation. This epic sprouts from (one of) the most ancient civilisations in the world, and is therefor both an important political document where humanity is shown both the splendour and dangers of civilisation. In this “civilised man” is hidden a shadow who comes in story after story as the demon or trickster that lurks the King into unwise decisions that eventually causes his downfall. In many ways, it is a macrocosmic application of the study of the shadow of the individuality of man, but described at the collective level of a civilisation.

We could say that it was Shah’s shadow that came from the backdoor and tricked him and his people as he became too serious, rigid, ambitious and proud in his ambitions. As he strived to modernise Iran through the “White Revolution” which initiated a series of reforms that would lift the “primitive and simple folk” of the rural areas into a rapid growth toward modernisations of all kinds, a collective shadow started to constellate where the inferior and uncivilised aspects of the collective culminated in a disloyalty and hostility toward the Shah at one of the most critical moments of his rule. The generational clash became too big as “the modern man” was freely roaming the Westernised streets of Tehran while his parents still lived in simple traditional clay-house villages on the rural side. While he encountered women in mini-skirts and naked love-making scenes in the city-cinemas, his father still thought of women as second-class citizens who had to obey to the superiority of their husbands and fathers. This clash became a split-off shadow for many of the young men (as well as women) in Iran, who then unconsciously were pulled toward the image of the Imam, a figure that could bridge the gap in their psyche between them and their fathers. One of the other reasons why the shadow constellated was because Shah did not create the container nor allow the space to be mocked, to be corrected in his arrogance and pride as the “King of Kings” of Persia. It is this inflations attitude—with dictatorial traits, not uncommon in the world at that time—that invited the shadow force to strike him.

The Trickster as Shamanic Consciousness

So who and what is then, this trickster shadow in the most elevated form for the Iranian civilised King? For this question we have to dive into the deep history of Iran, and find the severance that took place in the collective psyche that was two-fold but in relationship to one another. The first is the birth of Zoroastrian religion, which is known as the first dualistic religion in the world that brought a transcendent aspect of a God of Light and Wisdom who had its counterpart and evil shadow. This was the dawn of consciousness in the modern man, and it is in fact the root of Jung’s individuation concept; the human being who is able to differentiate and separate from the crowd and find his/her own individual light, consciousness and purpose. But this great shift in human consciousness came with a price—the severance from the collective, hive-mind and ultimately the separation from the World Soul. In the tradition of alchemy, the separation and transformation of the individual has to result in the return to a union with the World Soul, the so-called Rubedo stage. But as Jung writes throughout his work, this is a highly difficult stage to arrive at. The trickster then, is here to pull-down the civilised man, back to the Earth from his glorious heights and remind him that he came from the earth and the mud, that despite his many human achievements, he is nothing special—he is a mere mortal that makes mistakes and has the primitive and so-called “lowly” qualities just like any other ordinary man.

Jiroft shaman with panthers

“snake-man” from the Jiroft civilization; represents a deity or shaman

On an even deeper level, the trickster invites back the civilised Iranian King who has severed himself from the Earth-rooted and shamanic spirituality that existed in Iran prior to Zoroastrian religion. In the ancient motifs and archaic finds in the ancient “Jiroft Civilisation” we see that the very first civilisation in Iran—who date back to the same time of the Sumerians—had not a monopolistic or even dualistic idea of religion but an earth-rooted polytheistic vision and experience of the sacred. The symbols that became symbols of the evil Ahriman in later Zoroastrian orthodoxy (snake and scorpion) had an important place in the sacred pantheon of this ancient civilisation found in Jiroft.

The Emergence of the Unconscious Opposite: Enantodromia

The revolutionaries of 1979 hoped to overthrow and move on from the dictatorship they experienced in the Shah. But unfortunately for an entire nation and the generations that came afterwards, the situation in Iran did not become lighter nor more free; on the contrary, it has only become more oppressive and dictatorial. It has indeed regressed from the modernised image and progress that Shah and the Pahlavi dynasty had made. The Ayatollahs did not learn from the dictatorial mistakes of the Shah and have only created a greater shadow force through their severe oppression of both women and the “modern, Western world”. As a result, the archetype of the trickster is played out and manifest in its most evil and dark aspects: corruption, deceit, propaganda and stealing of national recourses. The situation has grown so severe and stark that one cannot conclude otherwise that an enantiodromia [literally: “running counter to”] is taking place with the Woman-Life-Freedom movement; this movement and it’s three words describe everything the Islamic Republic has oppressed: the feminine, the natural flow of life and the freedom to be. Jung described enantodromia, psyche’s full swing to its opposite pole as “the emergence of the unconscious opposite in the course of time.”

“This characteristic phenomenon practically always occurs when an extreme, one-sided tendency dominates conscious life; in time an equally powerful counter position is built up, which first inhibits the conscious performance and subsequently breaks through the conscious control.”(5) — Carl Jung

Woman L:ife Freedom revolution artwork

It is exactly the extreme of attitude and suppression that is enabling one of the most remarkable revolutions in the history of our planet: a woman-entered and led revolution that has at its core values and principles that are rooted in life herself. And it is for this reason that although this revolution has caused so much pain and trauma for the average Iranian in and outside of Iran, our eyes are fixed on the movement and any moments of hopelessness and divide which the dictatorship has tried to contaminate the people with has survived for more than a few weeks. The phoenix of the Feminine in Iran is rising like volcanic eruption from the depths and everyone can feel it. In a recent survey done by the well-known independent organisation Gamaan, an overwhelming majority of Iranians (67% inside Iran and 90% outside Iran) feel that the Woman-Life-Freedom revolution will succeed and reach its goal and completion in the overthrowing of this regime. (6) It is perhaps this unfolding enantiodromia in the collective psyche that makes it so overwhelmingly easy to believe and hold on to the rapid currents of Woman-Life-Freedom that is not only aimed at changing a regime, but bring about an entire rebirth and transformation of the Iranian collective psyche—and eventually contribute to a shift towards Feminine forms of leadership in the larger global collective. I would like to conclude this essay with Jung’s understanding of the opposites and the transformation of consciousness:

““Every psychological extreme secretly contains its own opposite or stands in some sort of intimate and essential relation to it. Indeed, it is from this tension that it derives its peculiar dynamism. There is no hallowed custom that cannot on occasion turn into its opposite, and the more extreme a position is, the more easily may we expect an enantiodromia, a conversion of something into its opposite. The best is the most threatened with some devilish perversion just because it has done the most to suppress evil.”(7) ”